- Top-rated Best Lawyer in Ghaziabad

- +91 9616166166

- [email protected]

Do You Know the Process of Filing a Complaint Against Fraud?

May 25, 2025

How to Choose the Best Divorce Lawyer in Ghaziabad: A Complete Guide

May 28, 2025With the introduction of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), India has embarked on a historic and ambitious reform of its criminal justice framework. Replacing the over 50-year-old Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), 1973, the BNSS seeks to inject much-needed efficiency, transparency, uniformity, and accountability into the legal process. The CrPC, though revolutionary at the time of its inception, often fell short when it came to clearly defined procedural timelines, resulting in widespread delays, procedural abuse, judicial backlogs, and eventual denial or dilution of justice.

In today’s fast-paced, digitized world, legal efficiency is no longer a luxury—it’s a necessity. The BNSS addresses these long-standing issues by introducing clear, mandatory deadlines for various stages of investigation and prosecution. These timelines are not only meant to streamline police procedures but also to improve the victim experience, reduce pendency in courts, and ensure speedy trials, aligning with the principle that "justice delayed is justice denied."

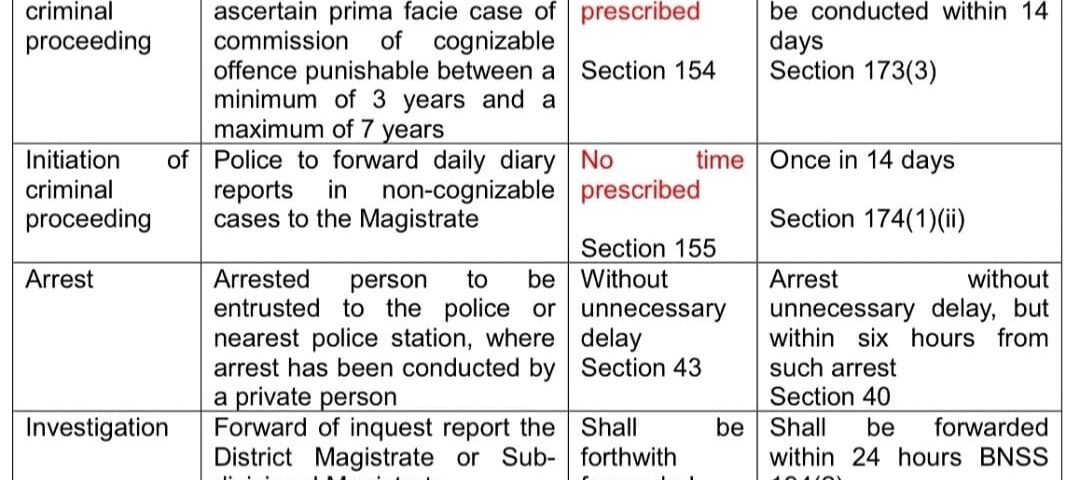

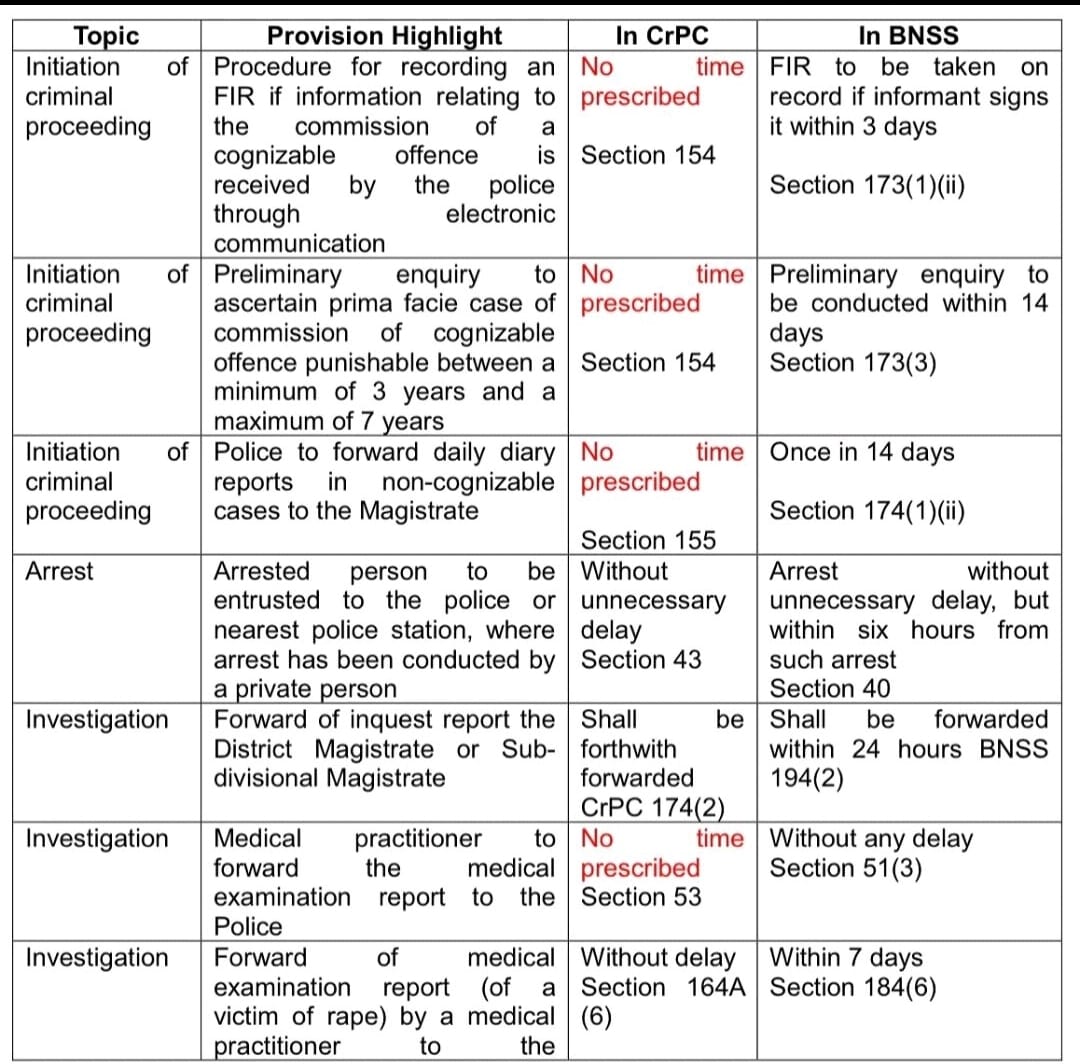

Below, we delve into the most critical differences between CrPC and BNSS that highlight how timelines in criminal procedures have been redefined to build a more responsive and responsible justice system:

1. Filing an FIR via Electronic Communication

🔹 CrPC:

Under Section 154, First Information Reports (FIRs) could be sent electronically—via email, SMS, online portals, or messaging platforms. However, the law did not specify how long the police could take to convert these into formal written complaints. This procedural ambiguity led to inconsistent handling across jurisdictions, lengthy delays in case registration, and left complainants—especially in cases of domestic violence, cybercrime, or financial fraud—feeling helpless and unheard.

🔹 BNSS:

Section 173(1)(ii) now provides a clear mechanism: it requires the complainant to physically sign the electronic FIR within three days for it to be legally recognized. If the informant fails to do so, the FIR is considered invalid. This ensures authenticity, discourages frivolous complaints, and integrates the convenience of digital submission with the formalities of due process.

👉 Why it matters:

This reform brings digital FIRs in line with legal protocols, bridging the gap between modern communication and legal authenticity. It protects both complainants and law enforcement from legal loopholes and promotes consistency and traceability in criminal reporting across all states and Union Territories.

2. Preliminary Enquiry for Cognizable Offences

🔹 CrPC:

Police had the discretion to conduct preliminary enquiries before filing an FIR for cognizable offences punishable with 3 to 7 years (like cheating, threats, or breach of trust). However, CrPC provided no stipulated deadline for these enquiries. This loophole allowed officials to indefinitely delay investigations, creating opportunities for corruption, favoritism, and suppression of legitimate complaints—especially those involving powerful individuals or organizations.

🔹 BNSS:

Section 173(3) addresses this vacuum by mandating that such preliminary enquiries must be completed within 14 days. The police must decide whether to register an FIR or drop the matter within this timeline, leaving no room for arbitrary delays or political interference.

👉 Why it matters:

This change is a major win for accountability and fair policing. It ensures that complaints are either acted upon or dismissed based on evidence, not discretion. Victims, especially from marginalized communities, will no longer have to wait endlessly for justice to begin.

3. Forwarding Daily Diary Reports in Non-Cognizable Cases

🔹 CrPC:

Section 155 required that daily diaries—records of non-cognizable offences—be submitted to the Magistrate, but it lacked clarity on frequency or deadlines. This vague language allowed for irregular submissions, compromising judicial oversight and diluting the seriousness of seemingly minor but impactful cases such as stalking, harassment, and verbal abuse.

🔹 BNSS:

Under Section 174(1)(ii), police are now required to submit these diary entries once every 14 days without fail. This creates a systematic check-and-balance mechanism, ensuring that Magistrates are regularly updated and can track whether appropriate action is being taken.

👉 Why it matters:

This reform enhances judicial vigilance and encourages more diligent record-keeping within police departments. It prevents lower-priority cases from falling through the cracks and upholds the rights of complainants in non-cognizable matters who often struggle for redress.

4. Arrest by Private Person

🔹 CrPC:

According to Section 43, a private citizen could arrest a person committing a cognizable offence but was only required to hand over the accused to the police “without unnecessary delay.” This subjective phrase lacked any time frame and left room for vigilantism, abuse of power, and custodial overreach by non-official actors.

🔹 BNSS:

Section 40 introduces a strict six-hour deadline to present the arrested individual before the nearest police station, providing legal boundaries and ensuring protection of personal liberty.

👉 Why it matters:

This change reinforces the rule of law by ensuring that even when a private person makes an arrest, it must conform to due process. It protects individuals from unlawful detention, false accusations, and the risk of mob justice in emotionally charged situations.

5. Forwarding Inquest Reports

🔹 CrPC:

In cases involving unnatural deaths, Section 174(2) required that inquest reports be submitted “forthwith” to senior Magistrates. However, this undefined term led to bureaucratic delays and stalled investigations in sensitive death cases, such as custodial deaths, suicides, or suspicious homicides.

🔹 BNSS:

Section 194(2) replaces vague language with a firm 24-hour deadline for forwarding the report. This ensures that evidence is preserved, the body is not tampered with, and Magistrates can initiate further proceedings without delay.

👉 Why it matters:

Time is critical in such cases. Delayed reporting can compromise forensic accuracy and create opportunities for manipulation. This reform helps ensure that justice in unnatural death cases begins promptly and without obfuscation.

6. Medical Report Submission by Doctors

🔹 CrPC:

While Section 53 allowed the police to request medical examination of an accused person, it did not specify how quickly the doctor needed to submit their report. This led to considerable lags, often rendering the medical evidence irrelevant or tampered by the time it reached court.

🔹 BNSS:

Section 51(3) now directs medical practitioners to forward reports “without any delay” after examination, emphasizing the urgency of medical documentation in criminal trials.

👉 Why it matters:

Swift submission of medical reports maintains evidentiary integrity, especially in cases involving intoxication, assault, or mental health. It enables judges and investigators to proceed with timely assessments based on accurate, unaltered information.

7. Medical Reports in Rape Cases

🔹 CrPC:

Section 164A(6) stipulated that the medical report of a rape victim should be submitted “without delay,” but it did not define what constituted “delay.” As a result, medical evidence—crucial for both prosecution and victim support—was often compromised or delayed indefinitely.

🔹 BNSS:

Section 184(6) now mandates that medical reports in rape cases be submitted within seven days, ensuring a standardized response time for all healthcare institutions involved in medico-legal cases.

👉 Why it matters:

This provision places the victim at the center of the justice process, ensuring that they receive timely medical and legal assistance. It also strengthens the prosecution’s case by making forensic and clinical evidence available during the early stages of investigation.

🔚 Final Thoughts: Towards a Timely, Transparent, and Trusted Criminal Justice System

The BNSS marks a paradigm shift in India’s criminal justice ecosystem. By replacing ambiguous and discretionary timelines with clear, binding deadlines, it empowers stakeholders—from police officers to judicial authorities—to deliver faster, fairer, and more citizen-centric justice.

These changes are not merely procedural upgrades. They reflect a philosophical shift towards prioritizing victim rights, judicial efficiency, and systemic integrity. The BNSS also aligns with global best practices by recognizing the importance of digital documentation, timely medical care, and real-time judicial monitoring.

As the BNSS comes into full force:

- Lawyers must adapt their litigation strategies to reflect the shorter procedural cycles.

- Police personnel must be retrained to meet the strict timelines and enhanced reporting requirements.

- Citizens must educate themselves about their updated rights and procedural safeguards.

In a system long plagued by backlogs and delays, the BNSS is a welcome revolution. But for its promise to be fully realized, implementation, awareness, and vigilance will be key. Understanding its nuances is not just a legal requirement—it is an essential civic responsibility.